This app spots earthquakes before seismic reports

A woman stands on the debris of collapsed houses after a fresh 7.3-magnitude earthquake struck Nepal, in Sankhu, May 12, 2015. Photo by Navesh Chitrakar/REUTERS

SAN FRANCISCO — Did you feel that? Being shaken by an earthquake can be terrifying, but that fear may serve as a great alert system for others. LastQuake is an app and website that detects earthquakes by monitoring web traffic, Tweets and Instragram-esque photos. By sifting through Internet data, this app can spot a damaging earthquake 15 to 20 minutes before seismic waves yield an official report through channels such as the U.S. Geological Survey.

"The Internet is the digital nervous system of the planet, and we're able to detect the slightest shaking because people are nervous," LastQuake co-creator Rémy Bossu told PBS NewsHour at the American Geophysical Union fall conference happening this week in San Francisco.

This virality-based system isn't meant to replace USGS reports, Bossu continued, but rather its alerts provide valuable minutes for people to escape vulnerable buildings that may collapse. But given some people are easily spooked, how does the system distinguish a true quake from the rumbling caused by a large dump truck?

To validate crowdsourced info, Bossu and his co-developers at the European Mediterranean Seismological Centre rely on three pillars of information. The first is flashsourcing, a data analysis technique that detects spikes in traffic to their website. Their facility serves as a repository, pulling earthquake data from international sources like the USGS and then creating reports on seismic threats. As a result, the site is often the first stop for those searching for information about an earthquake in Europe, Asia and even the U.S. The second pillar is "Twitter earthquake detection", a tool operated internally by the USGS. It filters through tweets for earthquake-related keywords in multiple languages. Alex Witze wrote a great description of the program for Nature News in July:

Tweets can arrive at the NEIC [National Earthquake Information Center] faster than seismic waves can reach recording stations. In 2012, a magnitude-4.0 jolt in Maine set off a stream of tweets from the region around the epicentre. Earle got an automatic text notification before the shaking spread across New England. "I was at Safeway buying groceries, and I knew about the quake, from nothing but Twitter data, before other people felt it," he says.

USGS doesn't immediately release reports from Twitter earthquake detection because of the fickle nature of its viral information. Seismic waves felt by the agency's sensors can't be faked, but an Internet troll could easily post a false warning on Twitter. Plus the bulk of Twitter's 320 million users live in developed countries, like the U.S., so the social media platform offers a limited scope of earthquake eyewitness reports in some regions.

That's why LastQuake's third pillar is eyewitness reports. Users of the smartphone app or website fill out picture-laden, multilingual questionnaires about the seismic event that they're feeling. The IP address of a person's web browser or a smartphone's geolocation offers the testimony that an earthquake happened in a precise location.

Three examples of thumbnail photos featured in questionnaires on the LastQuake app and European Mediterranean Seismological Centre website. The questionnaires boast a thumbnail photo to illustrate each of the 12 level of the European macroseismic scale. Courtesy of Rémy Bossu

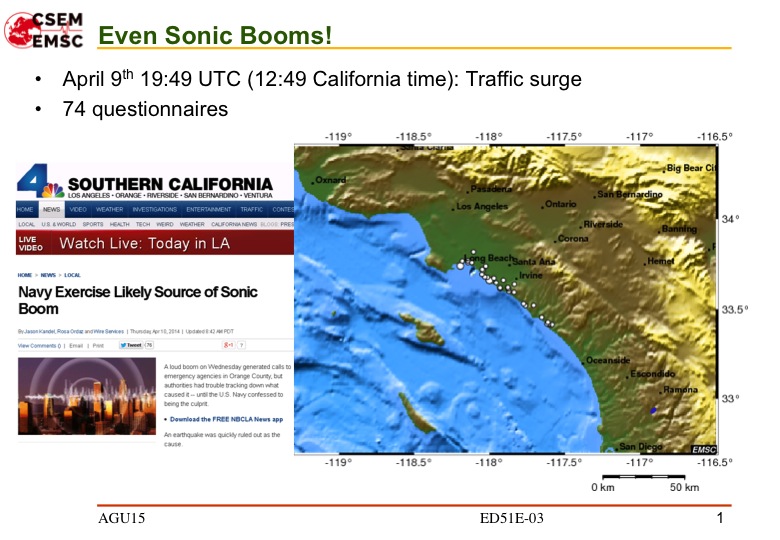

Combined, flashsourcing and Twitter earthquake detection can spot a seismic event within two minutes, and then a benchmark of three questionnaire testimonies validates the source. Users can also submit geo-tagged photos to warn other of the devastation, though the LastQuake team filters out graphic material. These testimonies help prevent false alarms, such as when a sonic boom rattled homes in California in April of 2014. Web traffic and social media posts painted the coastline, but they weren't backed by questionnaire testimonies, providing a filter for the system.

A slide from Rémy Bossu's LastQuake presentation shows how the app registered a web traffic spike in response to a Navy aerial exercise along the California coast in April 2014. Courtesy of Rémy Bossu

Since its release in July 2014, the LastQuake app has been downloaded by more than 100,000 people and has a 75 percent retention rate. Most users live in the U.S., Europe, Chile and India, but the goal is providing seismic alerts to people in remote locations.

LastQuake's first major test came when the 7.8 magnitude Ghorka earthquake shook the ground through Nepal, Bangladesh and India. LastQuake's popularity in India kicked into gear, allowing Bossu and his colleagues to register the event within five minutes and 18 seconds, and even though the program was less popular in Nepal, a spike flourished there within 10 minutes, according to a study published in October by the group. The first seismic-based warning from the USGS came 18 minutes and 16 seconds after the earthquake began.

Seismic waves (yellow and red lines) spawned eyewitness accounts (red circle) in the LastQuake app/website within minutes of Nepal's 7.8 M earthquake on April 25, 2015. Courtesy of Rémy Bossu

LastQuake's response time improved in Nepal to three minute and 16 seconds when a 7.3-magnitude aftershock moved the earth two weeks later. By surveying their users, Bossu and his team learned that the app's popularity had grown through word-of-mouth discussions among friends and social media. The majority of LastQuake visits from Nepal — 85 percent — came from mobile devices. The Earthquake app based on virality had itself become viral.

You may be wondering: "Wait, shouldn't an earthquake knock out cell phone towers?" The answer is no because communication infrastructure can be surprisingly resilient during a disaster.

"Even in extreme cases, the networks are pretty robust," Bossu said. "For instance in Nepal, all the cellphone towers have large generators and batteries for emergencies."

These generators are intended to support communication towers during Nepal's dry season, when power from the region's many hydroelectric dams drops. These independent generators can power a cell phone tower for 12 hours or longer during a crisis, Bossu said.

LastQuake isn't meant to replace official seismic reports about earthquakes, Bossu said, but the public warnings could pinpoint buildings with structural flaws, help prevent injuries and mobilize emergency teams. Going forward, Bossu's team plans to add new features to the app, such as multilingual notifications that detail what a person should and shouldn't do during a potential earthquake. Another idea is an "I am safe" button that alerts family members about a person's status. Red Cross disaster apps and Facebook host similar buttons for emergencies. The LastQuake team is also building an alert system for landslides, which often impair rescue operations.

"In the long run, we need an official app to cover all disasters," Bossu said.

--

__._,_.___

No comments:

Post a Comment