Dry wells and sinking ground as state struggles with groundwater crisis

PASO ROBLES, California – Two decades ago, the rolling hills of Paso Robles were mostly covered with golden grass and oak trees. Now the hills and valleys are blanketed with more than 32,000 acres of grapevines.

Surging demand for wine has brought an explosion of vineyards, and along with it heavy pumping of groundwater. With the water table dropping, many people have had to cope as their taps have sputtered and their wells have gone dry.

Drilling a new well can cost $30,000 or more, and for Juan Gavilanes and his family, that's out of reach. Instead, they're relying on a neighbor who lets them use his well, and they bring water to their house through a hose.

Standing in his parched yard, Gavilanes said life has changed radically. He let his vegetable garden die. His family uses a coin laundry. They take quick showers and eat on paper plates. He said it's quite clear where their water has gone and why their well is empty.

"The vineyards are killing us," said Gavilanes, a construction worker. "That's the problem, you know. They suck up all the water."

Groundwater levels have also been falling miles away, beneath the ranch of Kim Routh, who saw one of her wells dry up, and beneath the stables of Laurie Gage, whose horse-boarding farm relies on a well that can no longer pump as much anymore.

"I'm frightened, have been for a long time," Gage said, a hand resting on a steel corral. "I can point to three wells that have gone dry, and a fourth right down the road."

California's severe drought has multiplied the stresses on aquifers across the state, sending groundwater levels to record lows. But it's an issue that began long before the drought. For decades, through wet and dry periods, groundwater has been overpumped and progressively depleted.

The Central Valley alone is estimated to have lost more than 150 cubic kilometers of groundwater, roughly the amount of water in Lake Tahoe. Nearly two-thirds of that has been pumped out since 1960 as wells have proliferated. And the pace of depletion has been accelerating.

Even if El Niño brings a wet winter, it won't be enough to refill California's badly depleted aquifers. They've been drawn down so far that if pumping were suddenly cut back, the state would still need many years of above-normal rainfall and snows for a significant turnaround.

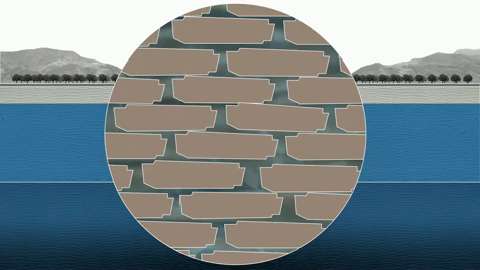

So much water has been pumped from the aquifer in the Central Valley that the underground spaces in layers of clay and rock have been collapsing, leaving the land surface permanently altered. Scientists have determined the ground is sinking faster than ever before, in some areas by up to 13 inches over just eight months. That settling has buckled the concrete lining of canals and damaged roads and bridges.

As the aquifers have receded, rural homeowners have been the first to run out. The state has tallied reports of more than 3,400 households out of water during the past two years, mostly with dry wells. Some of those homeowners have voiced resentment, blaming surrounding farmers with deeper wells for causing their predicament.

But along with the finger-pointing has come growing discussion about a fundamental imbalance: There are simply too many demands drawing on California's limited supply of water.

"We're running up against what I call 'peak water' limits," said Peter Gleick, president of the Pacific Institute, an organization based in Oakland that focuses on water issues. "There's no longer enough water to do everything that we want to do. We can no longer grow as much food as we're growing, as inefficiently as we're growing it. We can no longer ignore the fact that some of our agricultural practices are leading to problems."

When the communities' water sources suffer as a result, he said, "that's a problem of equity. It's a problem of power and politics. It's a problem of wealth."

Farmers have been spending heavily to drill new wells hundreds of feet down – even up to 2,000 feet deep in places – to reach water.

Property owners in California have long been entitled to draw as much water from their wells as they wish. In many areas, that lack of regulation has led to an unbridled free-for-all of pumping.

Trying to bring the situation under control, Gov. Jerry Brown last year signed the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, which puts local agencies in charge of managing groundwater and also gives the state new authority to step in when necessary to keep aquifers from falling further.

State officials have drawn up a list of 21 groundwater basins considered to be in "critical overdraft" and have laid out a timeline of requirements. By mid-2017, local "groundwater sustainability agencies" need to be formed. By 2020, basins that are in "critical overdraft" will be required to adopt 20-year plans for achieving sustainable management – defined as managing groundwater in ways that avoid problems such as chronic declines or saltwater intrusion.

Other high- or medium-priority groundwater basins will have until 2022 to have their groundwater plans in motion.

In the meantime, pumping has rolled along largely unchecked. Despite the drought, California farm revenues have risen to record highs in the past few years, pushing gross farming income to $56.9 billion in 2014. And it's been possible precisely because farmers have been leaning more than ever on the declining supply of groundwater.

"That gives them a short-term benefit, but the long-term consequences of that are going to be very severe, and we can't do that forever," Gleick said. "We have to ultimately think about how to bring the system back into balance."

In 1983, the Paso Robles area had a total of 17 wineries and about 5,000 acres of vineyards. By 1995, the number of wineries had grown to 29. Then the Central Coast suddenly became trendy as a winemaking region, and the number of wineries increased to more than 200.

That coincided with the expansion of the wine business across California, in places from Napa Valley and Sonoma County to Lodi and Temecula. The total number of licensed wineries in the state has grown from 944 in 1995 to 4,285 in 2014.

Winemakers and investors poured into Paso Robles partly for its climate – the sunny days, afternoon breezes from the Pacific Ocean, and cool nights. They planted many varieties: Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Syrah, Zinfandel, as well as others such as Mourvèdre, Grenache and Petit Verdot. Some vineyards imported vines from France.

As the business took off, it brought wine-tasting tours and lifted the economy of a town where businesses had been boarded up. Then came the declines in groundwater levels.

On her horse farm, Gage said the water level in her well has fallen about 130 feet since she moved to the area 27 years ago. When she last checked, the water level was 220 feet underground. In the past seven years, it has dropped at least 70 feet.

Her well now runs intermittently. After about 15 minutes of use, the pump automatically shuts down, and it only restarts an hour later once enough water has seeped back into the well.

As she carried armfuls of hay to feed her horses, Gage explained how she's using water sparingly while trying to keep her mulberry and sycamore trees alive. Without changes to the status quo, she said, "more wells will be going dry."

In 2013, as dozens of homeowners' wells were failing, concerned residents formed a group called PRO Water Equity and began advocating for changes to protect the water supply. At first, they were sharply at odds with wine grape growers, and their disagreements fed distrust.

Reacting to the complaints of many dry wells, San Luis Obispo County supervisors passed an emergency ordinance in August 2013 that for a two-year period barred new or expanded vineyards in the Paso Robles basin unless the additional water use could be offset with reductions elsewhere.

Gage, who is vice president of PRO Water Equity, said the contentious atmosphere changed after county supervisor Frank Mecham offered an idea to her group and the opposing side, a group of growers known as the Paso Robles Agricultural Alliance for Groundwater Solutions. He suggested they get together to search for common ground, and after a series of meetings they struck a compromise: a proposal to create a new water district to manage the groundwater basin, with a board that would include representatives of large-, medium- and small-sized landowners, as well as members elected by all voters.

"I've come to a much different understanding and appreciation of those guys as people," Gage said. "There is at least a fairly large group of wine grape growers who have come to the realization that unless we do something smart with our water soon, they're going to be in a world of hurt in terms of their investment. They've got huge investments in these areas, just gigantic, and they will lose all of that if the water goes away."

Nearby at Pomar Junction Vineyard and Winery in Templeton, owner Dana Merrill said he agrees the area should have its own district to start managing groundwater.

"Right now there aren't any rules," Merrill said. "You've got to start before it's an emergency."

The water levels in his vineyard's wells have been dropping. But Merrill, a 7th generation farmer and Californian, said he believes someday the wine country of Paso Robles can be as valuable as the vineyards of Napa and Sonoma.

"What is the one thing that could derail that? Running out of water," he said. "To me, how can you take a chance on screwing this up?"

Driving to the top of a hill, he looked out over rows of his grapevines and other vineyards in the valley below.

"I think we should do something about it," he said. "I don't want to sit here and say, 'God, maybe I should have done something about that.' Yeah, doggone it. Maybe there was a problem, yeah."

The proposal to create the Paso Robles Basin Water District will go before voters in an election on March 8, with three separate votes on creating the district, establishing a special tax to fund it, and electing its board of directors.

The proposal is generating controversy. One group of vineyard owners and other residents called Protect Our Water Rights is opposing the creation of a water district. They've gone to court to pursue an adjudication of the basin, which they argue would lead to a better court-supervised solution.

Gage doesn't see that as a workable approach.

"There's a lot of people who are so tied up in their concept of property rights that they can't envision that anybody would ever say to them, 'Guess what? You need to cut back,'" Gage said. "And without some kind of community consensus, it's going to keep going the way it's going."

The county's Board of Supervisors, meanwhile, amended the land use ordinance in October to make permanent its restrictions, which bar new vineyards or other water-using development in the Paso Robles basin unless water use elsewhere can be retired in exchange. If a vineyard intends to drill a new well, it needs to show it can conserve an equivalent amount of groundwater by taking out a more water-intensive crop or taking other steps.

"It's a way of saying look, we can't let people plant acre after acre, hundreds of acres of wine grapes, without doing something to offset that water use," said Bruce Gibson, one of the county supervisors who backed the change in a contentious 3-2 vote. "We have a serious problem with groundwater, and I think most people recognize this now. If we don't do something, we're going to hit the wall somewhere down the line."

The effects of drilling deeper go beyond higher pumping costs. In the Paso Robles area, the aquifer is made up of multiple layers of water and rocks, and at lower levels those layers can contain water tainted with high levels of boron, chlorides and other natural contaminants that can make it unfit for human consumption or use in agriculture unless it's treated.

The county measures affect only the Paso Robles groundwater basin. Just outside that area, near Atascadero, there are no restrictions and vineyards are still being planted. On a recent morning, workers moved along the rows on a hillside slipping plastic tubes over newly planted vines.

Kim Routh has also seen new vineyards spring up on the winding roads around her ranch. When a vineyard was established years ago directly across the road, one of her wells went dry within a month. She had used water from that well to fill a round basin and a watering trough for her cattle. Without that source, she said she decided to reduce the number of cattle she raises.

"This area was never meant to sustain this level of development," Routh said, standing near the empty basin in the dry grass. "One of the main problems I see is that people come into an area with a lot of money and they can afford to spend a lot of money to drill a well 1,000 feet deep."

"The large corporations come in and pump like crazy," she said. "And the people who live in the area can't afford to go that deep."

Her ranch is located in an unincorporated area where the county's measures don't apply, and she said winemaking companies have been buying up land all around to take advantage of the lack of regulation. Routh has been appalled to see that even as people have been struggling with dry wells, new vineyards have been planted.

"Money has taken over and crushed all common sense," she said.

Standing beneath an old windmill, Routh said she sees a real threat of completely running out of water.

"Sad. There used to be so much water here. It literally shot out of that well head," she said, looking up at the windmill, which was squeaking as the blades slowly turned.

"A lot of people don't want to talk about it because they don't want to upset their neighbors," Routh said. "I used to try to keep my head in the sand, but I can't anymore because it's just crashing in on us."

Highway 99 cuts through the heart of the San Joaquin Valley, passing fields of bare earth where dust devils whirl beneath the cloudless sky.

The alluvial soil spreads out as flat as a lake and meets patches of green that stretch into the distance and fade in the hazy air. In the 1800s, there was a giant lake here, Tulare Lake, which was fringed with marshes. But its waters were diverted to farms more than a century ago, and the lakebed was transformed into fields.

Along the road, farms roll past in a blur: fields of cotton, orange groves, dairies, grapevines, and orchards of nectarines, peaches, walnuts, pistachios and almonds. Among them are pipes that gush water into standpipes.

This portion of the Central Valley south of the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta lies at the epicenter of the state's problems of groundwater depletion. Tulare County has led the state with, at last count, about 1,900 dry wells in less than two years.

One of those wells stopped flowing at the home of farmworkers Enrique Olivera and Yolanda Galvan, in a neighborhood flanked by walnut orchards near Visalia. For the first few months, neighbors let them use water through a hose from their well. Then they signed up to receive a water tank, and regular water deliveries by tanker truck, through a program supported by the state and the county.

As workers connected the new tank to their household pipes, Galvan said she is grateful to have the tank because her family can't afford to drill another well. But she also expressed aggravation that she's been struggling to keep her fruit trees alive while across the street a farmer's well pours out a steady stream into the mouth of a large standpipe day and night.

"The farmers are using much more water than residents like us," Galvan said, sitting on her porch while her 3-year-old son pedaled his tricycle in circles.

"They're stealing water from us, because they're using too much water. They should change their irrigation systems. Because the field here in front of us, they turn on the water and they let the water run," Galvan said. "They're using a lot in order to get rich, and they're leaving us without water."

Farmers in Tulare County deny those accusations, saying they've had surface water taken away from them by court rulings and the decisions of government officials who have curtailed water deliveries from the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta to protect the endangered delta smelt and other fish.

Farmer Mike Faria called it a "government-induced drought" on top of the natural drought. He said that while the declines in groundwater are worrying, farmers' hands are tied because of the reductions in flows through canals.

"Everybody is using groundwater. That's how we sustain ourselves through a dry time where there is no surface water," said Faria, whose family runs a 3,500-acre farm and five dairies in Tipton. "We're all pumping from the same bowl. We all got straws in the ground."

Previously the Farias could count on surface water to meet a portion of their needs, but those flows have disappeared. And Faria said it's been a struggle to adapt. Several wells have failed, and they've invested in deeper wells. Still, they have less water to work with.

"We had to sacrifice some land in order to take care of the rest of it," Faria said, standing on a fallow field covered with dry stubble left behind from the last crop.

His father Danny Faria, Sr., looked out across the parched field and kicked a weed with his boot, dislodging it and sending dust swirling. He said they aren't farming about 13 percent of their land because they don't have the water for it this year.

"The only way to recharge the water is the surface water," the elder Faria said.

"We need more surface water, more dams to hold water in wet years," he said. "If you don't have surface water, you use groundwater."

He said he deeply disagrees with the state government's approach. And if he could pick up and leave California for somewhere else, he would.

As for regulating groundwater, he said: "I can't stand the idea, but I know it's coming."

Nearby in the community of East Porterville, the front yards of farmworkers' homes are filled with brown grass and withered shrubs. The city of Porterville's deep wells have kept flowing, but in this unincorporated area just outside city limits, the water table has fallen below the reach of shallow wells and entire blocks have been left without running water. Tanks have been installed in front of many homes.

Some people in East Porterville now make regular trips to a community water station, where they unravel hoses to fill up their tanks and barrels on the beds of pickup trucks and trailers.

Diego Bedolla, a 15-year-old who was helping his father fill two plastic barrels, said their well is running low and the water comes out with sand in it. When they get the barrels home, they carry the water inside with buckets to use for washing dishes, washing clothes and bathing.

"It's a lot of work," he said. "The buckets aren't that heavy, but it gets tiring when you do it for a while."

In the past, water from the Lake Success reservoir would normally flow down through the Tule River and recharge the aquifer around East Porterville. The drought has driven the reservoir's levels to record lows. Some water has continued to flow out of Lake Success, but it's diverted through concrete-lined ditches to farms that hold senior water rights. Nothing has been left to flow downstream alongside East Porterville. The riverbed sits bone dry, and that has eliminated a source of recharge for the aquifer.

At a church parking lot in East Porterville, the county government has set up an emergency drought center with a trailer where residents can take showers.

A local charity, the Porterville Area Coordinating Council, has organized events to hand out donated bottled water. At times, residents have lined up bumper-to-bumper in cars and trucks beside an old lemon packing house to receive cases of drinking water.

The volunteers doling out water include Ron and Cheryl Perine, whose well stopped working last year in a neighborhood where the biggest water users are fruit and nut orchards.

Ron hauled tanks of water on a trailer for months, and for a time was lugging buckets around the house before they took out loans to drill a deeper well.

"We'll be the rest of our life paying for the well – $600 a month," Ron said. The payments are stretching a family income consisting of Social Security payments and his disability benefits as a Vietnam veteran.

"I know a lot of people who don't think it's a crisis like a hurricane or volcanoes or earthquakes," Ron said, "but if you're in it like this, it is. It's a crisis."

The Perines' new well is 300 feet deep. But Cheryl said they still worry about what would happen if the water table keeps dropping.

"It's just unsure what's going to happen and how long it's going to last. Because if we have to drill another well, we're done," she said. "It's in God's hands, because financially we can't afford to do it again."

On highways cutting through farmland, large signs appear: "No Water = No Jobs" and "Help! Solve the Water Crisis."

The signs reflect the political fights over surface water from the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta that have roiled California politics for decades. And those fights have intensified as the drought has persisted.

"There's a lot of water that's going through the bay that should be coming down here," said Bill Gargan, president of the well-drilling business Kaweah Pump Inc.

"These farmers, our customers, they don't want to deplete the groundwater. That's their lifeblood," Gargan said, standing next to a drilling rig as it bored a new 400-foot-deep well.

"They wouldn't be turning these pumps on, and having it cost them so much money to run these pumps, if they had surface water to where they could use a smaller pump with less power," he said.

Farmers around Visalia have been spending $160,000 to $180,000 for new wells, Gargan said, while deeper wells in the western portion of the valley can run $300,000 to $500,000.

"We're getting probably like 30 calls a day," Gargan said. "The waiting list for a well right now is about a year and three months."

The demand is so strong that some drillers have moved to California from other states. Drilling rigs have been humming day and night, boring holes deeper than ever before.

In parts of the San Joaquin Valley, groundwater levels have fallen more than 100 feet below their previous record lows.

The state's list of areas in "critical overdraft" also includes places across California ranging from Merced to Oxnard, and from Paso Robles to the desert of the Borrego Valley in eastern San Diego County.

Water levels in wells have fallen by more than 100 feet since 1995 in parts of Fresno, Kern, Los Angeles, Riverside and San Bernardino counties, according to U.S. Geological Survey data.

Major declines have occurred not only in California but also in places across the western United States. Researchers at the University of California, Irvine, and NASA found in one study that groundwater has been rapidly depleted in the Colorado River basin, accounting for three-fourths of the region's total losses of freshwater – which also included losses from rivers and reservoirs – between 2004 and 2013.

They estimated that 50.1 cubic kilometers of groundwater was depleted from the basin during that period, far surpassing the amount of surface water losses from Lake Powell and Lake Mead.

Groundwater and surface water are connected. During dry seasons, flows emerging from aquifers sustain many streams and rivers. Groundwater also reaches the surface in natural springs. When aquifers decline, flows in streams can decrease. Springs can dwindle and dry up, as they have in parts of the desert in Southern California.

Last winter California had the smallest snowpack ever recorded in the Sierra Nevada. Long-term decreases in snowpack due to global warming pose threats to a water system that was designed for a different climate. And if combined with serious depletion of groundwater, both of those changes could make the state's water situation even more precarious.

But if groundwater can be managed better and levels are allowed to recover, scientists have said it would provide an important reserve for dry times and make California more water-secure as the climate warms.

The Union of Concerned Scientists has advocated what it calls a "big water supply shift" in California to focus on making groundwater supplies sustainable.

"It will be critical to achieve a better balance by refilling our groundwater account during wet periods for use during dry periods," the nonprofit group said in a report. It said that will involve redesigning systems to better capture water from storms and building infrastructure to replenish aquifers.

The group also called for better measurement and monitoring, saying that's vital to managing groundwater.

The problem for California is that the water deficit has grown so large.

NASA and UC Irvine researchers have estimated using satellite data that the Sacramento and San Joaquin River basins have lost 15 cubic kilometers of freshwater each year of the drought since 2011, with about two-thirds of those losses due to groundwater pumping.

The state would need multiple wet winters and at least 12 trillion gallons of additional water in its reservoirs, snowpack and aquifers to emerge from the drought, said Jay Famiglietti, a UC Irvine hydrologist and senior water scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Even then, depleted aquifers would take much longer to recover.

And one of the moral problems, he said, is that it's perfectly legal for those who can afford it to keep drilling deeper, while others are left dry.

"What that means is that only the wealthier individuals and the bigger farms will be able to survive with respect to groundwater, and that's unfair," he said. "It's become this true tragedy of the commons and a race to the bottom of the Central Valley."

Back in 1977, U.S. Geological Survey scientist Joseph F. Poland posed next to a telephone pole in the San Joaquin Valley for a photo to illustrate the findings of his research. That image has since become famous. Near the top of the pole was a sign marking where the surface of the ground sat in 1925, about 30 feet higher.

Since then, a series of canals was built to bring water to the area, and the sinking of the ground slowed. But it has continued elsewhere, and has accelerated in other parts of the San Joaquin Valley during the past few years.

It's also a problem in places across the country and around the world where groundwater is excessively pumped from aquifers that are made up of fine-grained alluvial sediments and clay. Well-known cases of sinking ground, or land subsidence, have also occurred in Mexico City, Bangkok, the Houston-Galveston area and the Las Vegas Valley.

Across the United States, scientists have found subsidence is occurring in portions of 45 states covering more than 17,000 square miles. In some places where the ground has settled, buildings and pipes have been cracked and damaged, roads have buckled, the steel casings of wells have pushed out of the ground, and canals and bridges have been left needing costly repairs.

In parts of the Coachella Valley in Southern California, the ground sank by between nine inches and 2 feet from 1995 to 2010. In the 1990s, cracks began showing up in homes, swimming pools and roads in some areas of La Quinta. In recent years, there have been fewer reports of damage in that area, apparently because the Coachella Valley Water District has been using water from the Colorado River to help replenish the aquifer nearby.

The most rapid subsidence in the state has been occurring in the San Joaquin Valley, where USGS hydrologists Claudia Faunt and Michelle Sneed have been tracking the problem. They've been using satellite images, measurements of groundwater levels and also a network of devices called extensometers to quantify the compaction of the aquifer.

"In the last month, it's shown about a half an inch of compaction at this location," Sneed said after examining an extensometer in a shed next to the Delta-Mendota Canal. "It is cranking. It's like changing every minute."

She rolled out a large measuring tape to check the depth of an adjacent well, while Faunt jotted the measurements. Then they found a spot along the canal where the concrete lining was cracked and jutting upward.

"This has been a problematic area for subsidence," Sneed said. In areas where canals sink, it can reduce or disrupt the flow of water. The long-term costs of fixing such problems haven't been comprehensively tallied, but they're substantial.

Sneed stopped at a bridge crossing another canal. At first glance, the bridge appeared normal. Then she pointed out that the water has risen higher than the base of the bridge. Off to the side of the bridge, water was seeping out and formed a muddy strip along the road.

"As subsidence has occurred, the bridge has come down," she said. "The water surface is higher than the bridge and this bridge has to be replaced."

Land subsidence is explained by Michelle Sneed of the USGS. Steve Elfers, Jerry Mosemak

As groundwater has been pumped out, "lenses" of clay have compacted and rearranged themselves, Faunt explained, so that they become flat "like a stack of dinner plates."Faunt explained how it's happening, starting with the geology of the Central Valley's aquifer system. The valley's alluvial soil began as sand, gravel and clay that washed down from the Sierra Nevada and the coastal ranges. Think of a bathtub filled with layers of sand, rocks and clay, and water that has flowed down from the mountains and seeped in over tens of thousands of years.

When that occurs, as it has across the Central Valley, the aquifer becomes compacted and its water-storing capacity is permanently reduced.

"If you think of where we are now, the land surface used to be about 4 feet over my head," Faunt said. "The land has subsided about 10 feet here."

The ground level has followed the aquifer's levels, which in some areas have fallen a total of 300-400 feet, Faunt said. The most severe sinking has recently occurred near the town of El Nido, and farmers have been drilling wells as deep as 2,000 feet to reach the receding water.

Faunt and other researchers have estimated the rate of depletion from the Central Valley at about 1.85 cubic kilometers per year on average since 1960. Each year, that's a loss of enough water to fill about 740,000 Olympic-size swimming pools. During the latest four-year drought, though, they've calculated groundwater is being depleted much faster, at about twice that rate.

While farms have become more water-efficient over the years, there also has been rapid growth in the planting of higher-value crops such as fruit and nut orchards and vineyards. Those permanent crops have the effect of making the demand for water less flexible in the long-run because they require year-round irrigation and unlike other crops cannot be left fallow in dry times.

"To reverse the trend I think is going to take a lot of things. The simple answer is we need to reduce groundwater pumping," Faunt said. "We need to basically balance that bank account."

Moving in that direction can be achieved by either reducing the amount of overdraft or recharging aquifers with flows of surface water.

"We really need to think about what we're doing in between droughts and how to manage the water and get water into the ground between the droughts," Faunt said.

In each area of the state, a different set of remedies could help depending on the severity of the overdraft, the symptoms and the availability of other water sources. If the state's Sustainable Groundwater Management Act works as intended, it could be a historic opportunity for communities with badly depleted aquifers to come up with their own solutions.

"It puts it squarely on the locals to get it done, or the big bad state will step in and do it for them, but it also gave them tools," said Felicia Marcus, chair of the State Water Resources Control Board. "Your goal is to give the locals the political will to do it themselves."

The proposal in Paso Robles to create a new agency to manage groundwater will be closely watched across the state, and supporters say it could be a model for how an area can find compromises to address severe depletion.

Gleick, of the Pacific Institute, said he thinks the timetable of allowing agencies until 2040 to achieve plans for sustainable management is much too slow. He has recommended speeding up the pace, including moving more quickly to improve measurement and monitoring.

"We need to know how much water is actually being withdrawn and who's taking it," Gleick said. "As long as we're not measuring and monitoring all groundwater uses, those people who can afford to drill deeper wells, those people who can afford to pump more, will benefit from that lack of control."

And as pumping costs continue to escalate, some farmers could eventually be forced to reduce irrigation or stop pumping altogether, the same way they've shut off their wells in parts of Texas and Kansas that rely on the Ogallala Aquifer.

The answer for California, Gleick said, can no longer simply be "find more surface water." The reason, he said, is that water from streams and rivers is already heavily used, and taking more would seriously harm ecosystems.

"We might be able to squeeze a little more water out of the surface systems that we've built in California, but that's not the long-run answer," Gleick said. "The truth is in many parts of California we're already taking too much water out of our surface systems."

In the big picture, Gleick said he recommends three solutions for dealing with groundwater overdraft:

1). Figuring out how to manage surface water better in order to prevent overdraft and boost groundwater levels. That includes capturing more runoff during intense storms to recharge aquifers.

2). Finding ways to use groundwater more efficiently and grow more food with less water. That includes improving irrigation systems, changing the mix of crops and growing less water-intensive crops.

3). Cutting back on pumping where it's necessary. In some places, he said, people are simply taking too much out of the system and "the only way to bring it back into balance is to reduce what we're doing."

He said those recommendations apply not only to California but to more and more parts of the world where groundwater overdraft is worsening and ultimately is unsustainable.

This increasingly serious problem, he said, has been long underappreciated and neglected, but it can no longer be ignored.

USA TODAY Investigative Reporter Steve Reilly contributed to this report.

This special report was produced with a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

Source: http://www.desertsun.com/story/news/environment/2015/12/10/california-overdraft/76372340/__._,_.___

No comments:

Post a Comment