Why is the Sun's corona so hot? Two words: Solar tornadoes

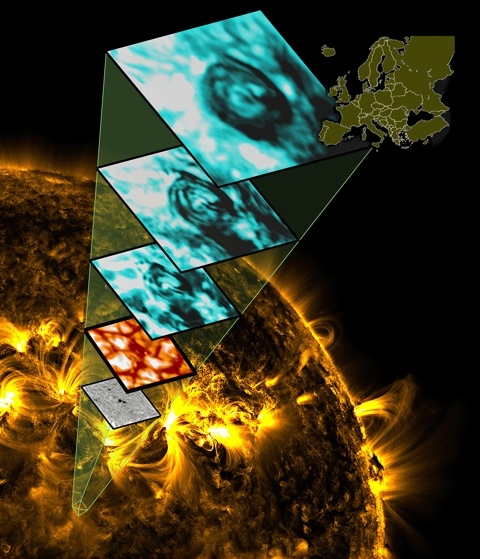

Five different wavelengths of light reveal a vortex of gas in the Sun's atmosphere. This swirling gas may be the result of intense magnetic fields and may explain why the Sun's corona is so hot.

Scullion, Wedemeyer-Böhm et al.(2012); Background image: NASA

One of the abiding mysteries surrounding our Sun is understanding how the corona gets so hot. The Sun's surface, which emits almost all the visible light, is about 5800 Kelvins. The surrounding corona rises to over a million K, but the heating process has not been identified. Most solar physicists suspect the process is magnetic, since the strong magnetic fields at the Sun's surface drive much of the solar weather (including sunspots, coronal loops, prominences, and mass ejections). However, the diffuse solar atmosphere is magnetically too quiet on the large scales. The recent discovery of atmospheric "tornadoes"—swirls of gas over a thousand kilometers in diameter above the Sun's surface—may provide a possible answer.

As described in Nature, these vortices occur in the chromosphere (the layer of the Sun's atmosphere below the corona) and they are common. There are about 10 thousand swirls in evidence at any given time. Sven Wedemeyer-Böhm and colleagues identified the vortices using NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) spacecraft and the Swedish Solar Telescope (SST). They measured the shape of the swirls as a function of height in the atmosphere, determining they grow wider at higher elevations, with the whole structure aligned above a concentration of the magnetic field on the Sun's surface. Comparing these observations to computer simulations, the authors determined the vortices could be produced by a magnetic vortex exerting pressure on the gas in the atmosphere, accelerating it along a spiral trajectory up into the corona. Such acceleration could bring about the incredibly high temperatures observed in the Sun's outer atmosphere.

The Sun's atmosphere is divided into three major regions: the photosphere, the chromosphere, and the corona. The photosphere is the visible bit of the Sun, what we typically think of as the "surface." It exhibits the behavior of rising gas and photons from the solar interior, as well as magnetic phenomena such as sunspots. The chromosphere is far less dense but hotter; the corona ("crown") is still hotter and less dense, making an amorphous cloud around the sphere of the Sun. The chromosphere and corona are not seen without special equipment (except during total solar eclipses), but they can be studied with dedicated solar observatories.

To crack the problem of the super-hot corona, the researchers focused their attention on the chromosphere. Using data from SDO and SST, they measured the motion of various elements in the Sun's atmosphere (iron, calcium, and helium) via the Doppler effect. These different gases all exhibited vortex behavior, aligned with the same spot on the photosphere. The authors identified 14 vortices during a single 55-minute observing run, which lasted for an average of about 13 minutes. Based on these statistics, they determined the Sun should have at least 11,000 vortices on its surface at any given time, at least during periods of low sunspot activity.

Due to the different wavelengths of light the observers used, they were able to map the shape and speed of the vortices as a function of height in the chromosphere. They found the familiar tornado shape: tapered at the base, widening at the top, reaching diameters of 1500 km. Each vortex was aligned along a single axis over a bright spot in the photosphere, which is the sign of a concentration of magnetic field lines.

With that hint, they ran a series of computer simulations including both gas and magnetic effects. They found the processes in the photosphere funneled the magnetic field lines into knots of high concentration, which rotate as the gas itself circulates. (This is known as the "bathtub effect," since it rotates in a similar way to the vortex produced in a draining tub of water). The intensity of the magnetic field in turn forces the gas in the chromosphere to follow a spiral trajectory up and away from the Sun's surface, speeding it up during the process. Temperature is related to the average speed in a gas, so higher speeds mean higher temperatures—sufficient to explain the million-degree coronal temperatures.

The number of observed vortices is small, but the results from the current study are sufficiently interesting to merit follow-up observations. If the model holds up under further investigation, it could solve the problem that has plagued astronomers since they first characterized the corona in 1869.

Nature, 2012. DOI: 10.1038/nature11202 (About DOIs).

__._,_.___

No comments:

Post a Comment