If It's A Windy Day When A Big Quake Hits, Parts Of LA Could Burn To The Ocean

A non-earthquake-related fire in downtown in Los Angeles on December 8, 2014. (Robyn Beck/AFP/Getty Images)

A non-earthquake-related fire in downtown in Los Angeles on December 8, 2014. (Robyn Beck/AFP/Getty Images) In movies, when a big earthquake hits, the main danger always seems to be crumbling buildings. But in real life, the fires that follow earthquakes can be even more destructive.

When a quake shakes the ground, gas lines can be severed, power lines can collapse and electrical arcs can start fires as everything smashes together.

In San Francisco, in 1906, the resulting conflagration leveled 22,400 buildings. In 1995, in Japan's Kobe quake, 6,900 structures were damaged by fire. Even in the 1994 Northridge quake, which was relatively small, 110 fires started across the area, contributing to severe damage of 12,000 buildings.

"Any densely built up part of the Los Angeles metropolitan area is at risk of fire following earthquake," said Charles Scawthorn, co-president of SPA Risk, one of the world's leading fire following earthquake experts.

At night, a gas main on fire throws flames into the air after it broke and exploded destroying nearby homes following the Northridge earthquake, on January 17, 1994. (HAL GARB/AFP/Getty Images)

At night, a gas main on fire throws flames into the air after it broke and exploded destroying nearby homes following the Northridge earthquake, on January 17, 1994. (HAL GARB/AFP/Getty Images) However, according to a study conducted by Scawthorn's company for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, some of the most vulnerable parts of the city might not have enough water to fight the number of fires that break out when a big earthquake hits.

And, says Scawthorn, the results could be disastrous.

The report, titled "Planning Level Fire Following Earthquake Model for the City of Los Angeles," was obtained by LAist through public records requests.

FIGHT FIRE WITH WHAT WATER?

If the shaking is severe enough to sever gas lines, it can also break open water pipes.

In Los Angeles, the water system is vast, complex and old. About 65 to 70 percent of the distribution pipes are made of cast iron, and are vulnerable to earthquakes, according to Craig Davis, former water systems chief resilience officer for LADWP.

"We know from experience, from earthquakes around the world ... that they don't perform so well because they're kind of brittle. We get more breaks per mile in cast iron pipe than we would per mile of ductile iron pipe," he said.

When a water main breaks pipes can lose pressure, meaning when firefighters connect to hydrants nothing will come out.

"You're going to have the fires, but you're not going to have the water," said Scawthorn. "So, where do you get that water?"

Put simply, it depends on where you live.

L.A.'S POOLS SAVE LIVES

It was 4:31 a.m. when the 6.7 magnitude Northridge earthquake struck.

An hour later, on Balboa Boulevard in the San Fernando Valley, a man was sitting in his stalled pickup truck in a flood of water. Water mains had broken, but a gas main had broken as well.

When he turned his key, a spark ignited the invisible cloud around him. The fireball was large enough to set buildings on both sides of the street on fire.

Two fire engines driving by saw the incident and responded.

However, when the firefighters hooked up to a hydrant it was dry. The water that should've been coming out was gushing out on to the street because of the broken pipe.

They desperately needed to find another source of water before the entire block burned down.

And then they found it in someone's yard: a swimming pool.

In the end, it took 14,000 gallons of water - all of which was pumped from two nearby pools - to stop the fires from spreading.

They were lucky. The earthquake had hit the San Fernando Valley, which is uniquely positioned when it comes to fighting fires after earthquakes. Like good parking spots and big malls, pools are abundant.

Plus, the lots there are larger than in many other parts of the city. Houses are spread out and wide streets can act as natural fire breaks, stopping a conflagration from spreading.

"In the neighborhoods where there's a large number of swimming pools, they're in much better shape for reducing the spread of fires," said Scawthorn.

A "HOLOCAUST" IN SOUTH AND CENTRAL LOS ANGELES

It's a different story in South and Central L.A., which have the oldest infrastructure in the city and few alternative sources of water to draw from.

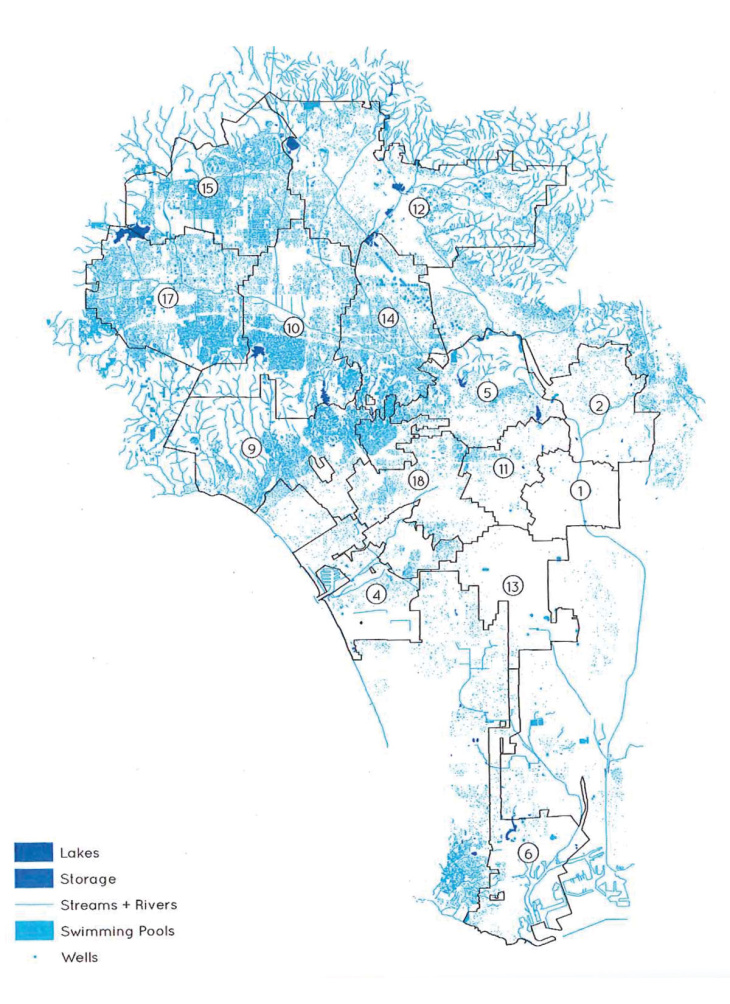

Alternative sources of water across Los Angeles, as illustrated in the 2016 report "Water, Water Not Everywhere," written for the Mayor's Office of Public Safety by D. Brittany Jang.

Alternative sources of water across Los Angeles, as illustrated in the 2016 report "Water, Water Not Everywhere," written for the Mayor's Office of Public Safety by D. Brittany Jang. Bottom line: There are few pools in South and Central Los Angeles.

Why? It has to do with how the area was developed decades ago and who lives there.

Discriminatory practices like redlining, which classified the area as "blighted" due to "subversive racial elements," meant that there was less likely to be investment in public infrastructure, including pools.

Developers were less likely to build there, and getting a loan to buy a home was also difficult, especially for people of color. For people who did secure loans, the lots in permitted areas were smaller, and had less space for private pools.

In later years, any public pools that were built were at the mercy of economic factors.

"[Public pools are] one of the first things that you see distressed neighborhoods of color cutting," said Nathan Connolly, Director of the program on racism, immigration and citizenship at Johns Hopkins University.

"They cut community centers, they cut access to parks, they cut access to pools. Those spending measures never really make it on to the docket."

However, it's not just the lack of pools that make the neighborhoods in South and Central L.A. more vulnerable to fire.

Unlike the Valley, the streets are tightly packed with low rise, wood frame, pre-1960s houses that fire can spread between easily.

Many of the houses are rented, not owned, which can mean residents have less control over whether properties are kept up to the latest seismic standards. Certain types of houses that haven't been retrofitted can slide off their foundations and break gas and power lines when a quake hits.

"Unfortunately when we looked into it, there's thousands of these [pre-1960 wood frame homes] across Los Angeles, across the older parts mostly, and only a few of them have been retrofitted," said Davis.

On top of all of that, the area has the highest concentration of above and below ground fuel storage tanks, which puts it at a greater risk of gas and oil fires, according to a different fire-related LADWP report from 2017.

In his 2019 report, Scawthorn assumes that there's little or no wind when fires break out. If a big quake hit during an event like the Santa Ana's, everything would change.

"If it's high winds, all bets are off," said Scawthorn. "What you have then, I mean that's a holocaust. What you have then is a Paradise situation in Central Los Angeles. It's just horrific. You know, the fire will burn to the ocean."

IT'S NOT JUST THE SAN ANDREAS FAULT

Not every large earthquake is going to set fire to every part of the city.

It depends on which fault slips, the location of the epicenter, and the size of the quake.

Scawthorn's report considers scenarios from a number of different faults, including the San Andreas, which is not expected to cause the largest number of fires within the city.

The largest number of fires are attributed to the Puente Hills fault, which runs right under some of the most densely populated parts of L.A. That fault, and the Newport-Inglewood fault, are the biggest threats to South and Central L.A. However, the odds of quakes on those faults aren't as high as along the San Andreas.

"These faults that are in the L.A. basin are like direct hits on the urban fabric of L.A.," said Ken Hudnut, geophysicist with the U.S. Geological Survey. "So, where you have strong shaking in close proximity to densely populated residential areas, you get lots of ignitions and it can be even more serious in terms of fire following earthquake."

To be clear, the San Andreas is no slouch.

A big one on it could result in an estimated 1600 ignitions spread out over much of Southern California.

Odds or not, any of them could slip at any time.

"Yes, we should worry about it," said Davis. "Do we necessarily have a problem in any given earthquake? No."

SOLUTIONS

Scawthorn's fire following earthquake report is part of a broader effort by city officials to better understand what needs to be done to improve the resilience of the water system.

"There's already been a long 50 year period of making significant improvements to pumping stations, treatment systems ... reservoirs," said Davis. "What hasn't been upgraded is the pipes."

The LADWP is currently replacing older, aging pipes with more seismically resilient ones as part of their normal upgrade program, but it's slow going.

Out of the 7,000 miles of old pipe, 14 miles of them will be replaced by 2020, according to Razmik Manoukian, water quality director at the organization.

At the current rate, it would take 120 years to replace all of the water pipes.

Given the slow speed of replacement, Manoukian said they're focusing on specific parts of the grid that'll give them a buffer in case of breakage after a quake.

"[The report] helps on the big picture, but it didn't shift what we're doing. It's going to refine what we're doing and it's going to improve our emergency response," he said.

When asked about the danger of water loss in South and Central L.A., he was more optimistic than Davis and Scawthorn. He said that unlike the San Fernando Valley, older parts of the city have a denser network of pipes running through them, meaning there are backup pipes if others fail.

In response, Davis, LADWP's former resilience officer said, "I don't like living on that type of a hope. If that's all we're hoping for, we've got problems."

Captain John Ignatzik, Disaster Preparedness Officer for the Los Angeles Fire Department, said they're also taking the report into consideration.

"I think it's just two different areas of town with hazards or threats and we need to adapt to two different areas," he said.

However, when a major quake hits, there might not be enough firefighters to immediately respond to the number of incidents.

Scawthorn has an even more radical idea for addressing issues of water loss in older parts of the city. He suggests a seismically resilient high pressure line that could draw water from the ocean and act as a backup for South L.A.. It's a similar idea to what San Francisco did after the 1906 quake.

"It would cost some money. Maybe a few tens of millions of dollars, but given the values at risk in Los Angeles, that's nothing. And it would provide a backup redundant water system," he said.

LADWP's Manoukian dismissed it as impractical.

The simpler solution Scawthorn suggests is to build more public pools.

"If you have half a dozen, a dozen of those scattered through Central and South Central Los Angeles, everyone is a winner," said Scawthorn.

Davis said that's an idea LADWP had discussed with city officials in the past.

As it turns out, two public pools are slated to open in historic South Central over the next year, according to councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson. Funds were finally made available to reopen them following their closure during the recession. Their reopening has nothing to do with reducing fire risk.

"Not one constituent has raised this as a concern," he said.

Correction: A previous version of this story said 150,000 structures burned down in the Kobe earthquake in Japan in 1995. The actual number of buildings destroyed in the earthquake was 150,000 — the total number of structures damaged by related fires was 6,900. LAist regrets the error.

--

Groups.io Links:

You receive all messages sent to this group.

View/Reply Online (#32199) | Reply To Group | Reply To Sender | Mute This Topic | New Topic

Your Subscription | Contact Group Owner | Unsubscribe [volcanomadness1@gmail.com]

No comments:

Post a Comment